by Michael E. Shea

Copyright 2010 by Michael E. Shea

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Please attribute copies or adaptations to Dungeon Master Tips by Michael E. Shea of SlyFlourish.com

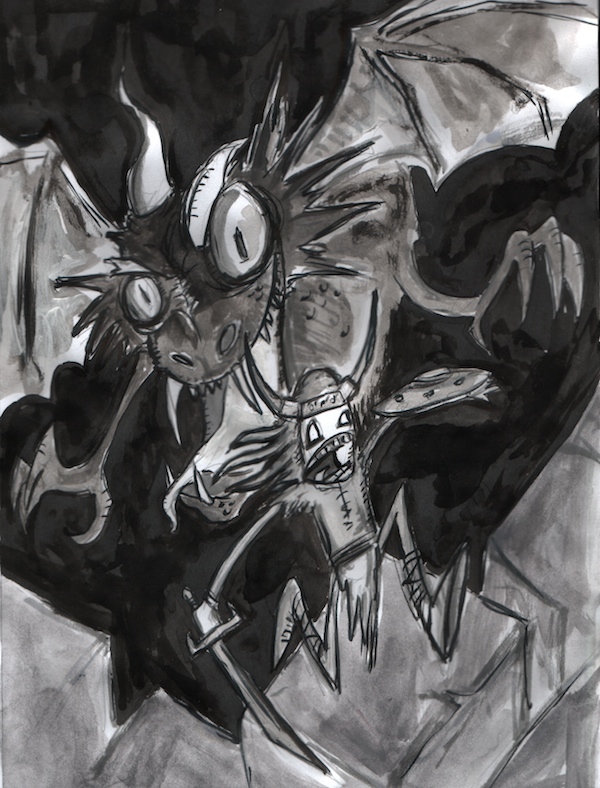

Cover and interior art Copyright 2010 by Jared von Hindman

First Printing July 2010

This book was originally written in 2010, during the early days of the fourth edition of Dungeons & Dragons and is focused mostly on that system. You'll notice this in some of the advice and some of the lingo in this book.

The spiritual successor to this book, Return of the Lazy Dungeon Master updates the ideas within Sly Flourish's Dungeon Master Tips with the experiences of thousands of GMs to help us focus on how we prepare our games, how we run our games, and how we think about our games.

The original Dungeon Master Tips still has useful and interesting advice but if you want my most current thoughts, experiences, and advice for the fifth edition of Dungeons & Dragons, pick up Return of the Lazy Dungeon Master.

I wrote this book to help you run awesome Dungeons & Dragons games. I wrote it assuming you've read both of the Dungeon Master Guides and have run a few games yourself.

This is a short book on purpose. It is designed to be readable in a couple of hours, even skim read in a few minutes. It is designed to act as a reference, offering checklists for designing your adventures, encounters, and battle maps. It is split into three sections: building your story, designing fun encounters, and running a great game. Throughout, you will find useful tools, tips, and advice you can use every time you prepare a game.

The first tip: If it doesn't fit, ignore it

In his 1946 essay "Politics and the English Language", George Orwell offers a rule that you should keep ready when reading the tips in this book too:

"Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous."

Part of being a great dungeon master is knowing which ideas and rules work well at your table and which do not. Consider all of the tips and advice in this book, but also consider whether this advice will work well for you and your group. Some tips may, some may not.

You will find few original ideas in this book. In the age of the web, we have access to a wealth of information and ideas that far outstretch what was available to us 30 years ago. With the combined experience of the best dungeon masters in the world on the net, we can now solve problems quickly and easily that, until now, have vexed us for years.

With that in mind, I have many people to thank for the ideas in this book. Many of them are writers who have as much a passion for Dungeons & Dragons as I do. They make the game far greater than the published books themselves, offering tips, tricks, and techniques that make our games better every day.

At the end of this book, in the acknowledgments, you will find a list of those who helped create and build upon the ideas that made this book possible.

Now let's start making your game better.

The most important adventure you will ever run is your very next one.

It's easy to find yourself spending most of your preparation time building out the details of your campaign world. You build armies of non-playing characters with whom your players can interact. You outline 100 tiny political threads going on in your living world. You write up 10,000 years of history and 50 different story seeds for your players to investigate.

All of that matters little compared to the next adventure you plan to run. You may enjoy building out that world, filling it with geographical, historical, and political detail, but little of it will likely hit your game table. Don't worry about the details of your massive new campaign, worry about how you're going to entertain the five people coming to your house next Thursday night.

Focus your attention on the stories, scenes, encounters, and challenges of the next game you plan to run. Worry about the story as it progresses, week by week, instead of building out huge branching flowcharts. Worry about the very next decisions your players might make in the next game you're going to run.

This may seem counterintuitive. After all, shouldn't we spend our time carefully planning out our campaigns? Detailed campaign plans end up either falling apart as your game progresses or make your game too rigid as you constantly force your players back to the track you had laid out for them.

Write out your campaign's elevator pitch

Write out a single-sentence description of your campaign. What is your campaign's central theme? What is the main concept behind your game? What is the one driving force that will move your players forward? Don't complicate it with four or five main purposes. We all love open worlds but having a single driving force is what keeps people moving forward. Consider the following campaign elevator pitches:

A single line campaign description is nearly all the planning you need to keep things moving in the right direction. From that seed, you can build 100 adventures that will last 3 years. All the while, your players will understand what it is they must do.

Use the 5x5 method

If you're not comfortable with a simple campaign elevator pitch and your wits to keep you building adventures, read up on http://critical-hits.com/2009/06/02/the-5x5-method/.

This is a simple method to build a rich, open world for your players to explore but still maintain enough structure to keep your game focused and give you a clear outline of adventures.

The process of the 5x5 method is simple. Begin with five central story lines that your campaign will follow. These should each sound like a campaign elevator pitch, big enough to keep your players busy but with a clear goal and direction.

For each of those five story lines, build out the five steps the party will take to get there. Each of these represents one to three game nights of adventures.

Finally, see how these different steps interconnect. What are the synergies that bring the entire campaign together? They don't all need these synergies, but a few will help your campaign feel cohesive.

Stay focused

Above all, stay focused on the things that are most important to your game. You may want to flesh out your final encounters to your big campaign but you would likely run a better game if you used that time to refine the battles that are coming up on your next game night.

Remember: Spend your time and energy on the game you're running next.

Every Dungeons & Dragons adventure has many moving parts. Unlike writing a story, you have many elements to consider to make sure your game is as good as it can be. A checklist can help you consider and keep track of all the possible elements that make a game great.

Below you'll find one such checklist. Review it each time you're putting together an adventure to help you remember all of the possible elements you may want to add to your game.

Here are the details of each item in the checklist.

Outline the adventure

Write out a loose outline for the adventure you plan to run. If you have any decision forks in your game, this is the place to describe those forks and their possible outcomes. A typical 4 hour game will probably have five main pieces including three combat encounters, a roleplaying encounter, and a skill challenge. This won't always be the case, but it's a good place to start. Add or remove elements as necessary to fit your plan.

A typical outline might look like this:

This short outline can keep you focused on the main scenes of your game. As you're building your adventure, you know what you need to fill out. At the table, it keeps you focused on the adventure's direction.

Build combat encounters

You will likely spend most of your preparation time designing unique combat encounters for your adventures. Encounters can be very detailed and precise, each with many moving parts.

Prepare non-playing characters (NPCs)

For each NPC your Player Characters (PCs) might encounter in your next session, keep track of this NPC's key traits such as backgrounds, desires, and fictional archetypes. Jotting them down on a 3x5 card can help you keep the information handy.

Prepare your miniatures

Pick out and prepare all of the miniatures you will need to run your battles. Have them separated out by encounter so you can quickly place them when the battle begins. Try using labeled zip-loc bags to separate miniatures by encounter.

Plan your skill challenges

Plan out and prepare each skill challenge your group will face in your next adventure. Consider what skills the players might use and write down the Difficult Checks (DCs) and bonuses that might apply.

Write flavor text

Write up any read-aloud text you need to describe the environments your PCs will experience. Writing good flavor text can help you fill in the details you might forget when ad-libbing at the table.

Prepare quest cards

Prepare cards for any quests the PCs might acquire. 3x5 note cards with quests written on them are a good physical reminder of players' current quests.

Calculate loot and experience

Prepare any loot and experience the party will earn in the next game.

Design puzzles

Puzzles are a good way to break away from the standard game mechanics but still include a specific challenge the players must overcome.

Prepare music

A good selection of music can keep your game entertaining. While you might gravitate towards classical, don't be afraid to add music of any genre to your playlist.

Develop props and handouts

Props and handouts are another way to keep your players tied into your game world. Use them whenever you can and whenever they fit.

Prepare table materials

Have ready all of the materials you will need at the table when you run your game. These include extra pencils, small dry-erase boards, marking rings, pipe cleaners, action point markers, and any other materials you need.

Every time you prepare for your game, run through this checklist to keep your games fresh, keep you focused on the important things, and save time at the table.

Making an exciting adventure every week is hard to do. You might rely on published adventures or you might build everything from scratch yourself, but either way, it's a challenge coming up with an entertaining game every week.

Have you ever wondered how Stephen King can hammer out so many books? Have you ever wondered how Jerry and Mike can come up with so many three-panel comic strips a year at Penny Arcade? There's a straight-forward answer, and it's critical if you're going to keep a good D&D game going every week for a long time. It comes down to two things: establishing routine and building within a structure.

Establish routines

In her book The Creative Habit, Twyla Tharp describes the rituals she follows in order to maintain a constant state of creativity in her life. Here's a woman whose producer tells her that she has a sold-out venue for a show in four months with a theme she hasn't even yet thought up. She begins with a very standard process, filling a banker's box full of ideas, snapshots, video tapes, and anything else that helps her begin to gel her idea. Though every show she runs is unique, her ritual is exactly the same.

This ritualized process is no different from DMs coming up with a solid adventure every week. The Creative Habit is an excellent take on creativity, and I highly recommend it to every dungeon master who takes their game seriously.

Mike and Jerry from Penny Arcade know they have to create a three-panel comic strip three times a week. Their routines for making the strip are consistent. Three times a week, Mike flops down on a couch, while Jerry sits at his Mac. They throw ideas back and forth until a three-panel story plays itself out. When it's ready, they switch positions. You can watch their routine on on the Fourth Panel series at PATV http://www.penny-arcade.com/patv/.

We, too, have our rituals, and the more we solidify the best of them, the more consistent our creativity will become. Where do you most often come up with new gaming ideas? How do you like to begin your adventure design? What inspires you?

The sooner you develop your routines for adventure design, the better you'll be at keeping up with a regular game.

Build within a structure

Like a three-act play or a haiku, a good game adventure has a structure. As you saw in the adventure checklist, there are specific components we need for our game. As you build adventures, work within this structure and fill in each of the components within.

It's always good to think outside of the box, but that doesn't mean you should forget about the box. Learning how to fill this box with a living and breathing world is as exciting as building a world without boundaries. Don't try to completely shake up your game world, limiting classes and races, changing the mechanics, and thinking too radically about your story. Remember that most players want to sit down at a table and have some fun. Stick to what they know and you'll all have a better time.

Constraint fuels creativity. Learn to love that constraint and love how you can build such an exciting story within three battles, some roleplaying, and a skill challenge.

In Stephen King's book On Writing, King talks about how storytellers let their characters grow from their own actions and motivations rather than from an overall plot or outline. This is often contradictory to what we've been taught and what we feel is the correct way to write a story. We want to outline a plot. We want to know where it's going and how it's going to get there.

Unfortunately, this is why most Hollywood movies suck. Popular film writers build an outline, and then force everything to fit within that outline regardless of how much more interesting it would be to let the characters drive the story. They don't want to let the story grow organically. They want control.

With D&D, we might feel that same dysfunctional drive. As Dungeon Masters, we want to know where the story is going. We want to have our campaign planned out so we know exactly what is going to happen. Unfortunately, this can lead to a stale and overdone story.

Build your story from the actions of your players

Instead, do what Stephen King does. Let the story grow organically from your players and their actions. Instead of plotting out your campaign, spend more time fleshing out your NPCs. Understand what drives and motivates them. Think about what they want and what they will do to get there.

Imagine your story as a pool table. Each pool ball is a NPC or PC. As they crash together, each goes off in their own previously unknown direction. Let your story grow from the collision of these balls, the interactions of your PCs and NPCs.

What you're left with is a rich and unpredictable story that unfolds from the motivations of your player characters, the actions of your players, and the reactions of your NPCs.

Provide off-camera stories

You might think that a lot of these generated NPC motivations, actions, and background are lost to your players who might not ever see them. However, you can expose these backgrounds directly to your players by writing a short story in an email. Show them the off-camera history or current actions of these NPCs. Reveal details in discoveries and conversations experienced by the PCs. There's nothing wrong with breaking the point of view from your PCs and giving your players a wider glimpse of the moving world around them.

Instead of spending your time building out a huge world, spend time building out your main NPCs. Rich and deep villains will end up filling out the details of a world through their actions. They will also remain memorable to your players and help advance the story. Think about who they are, what they want, and from where they came. Your players will never forget an interesting NPC.

See through their eyes

Close your eyes and think in the mind of the villain. Where is he right now at this point in the timeline of the story? What is he thinking? Where are they going to go? What is he wearing and who is he with? All of these details can give you a true feeling for the character. It makes him feel real to you. When he feels real to you, he feels real to your players as they interact with him.

Understand the moment that changed their lives

What moment in the NPC's background changed or defined his life? Consider the beginning of the movie X-Men where Magneto's parents are dragged off to the showers in a Nazi death camp and he is helpless to stop them. That is his defining moment, a moment that guides the rest of his life. What is that one moment for your NPC? Perhaps it is the death of a loved one. Perhaps it was a string of amazing luck. Perhaps it was the time he fell into a mine shaft and had to crawl out with two broken legs. Find that one moment in the lives of your NPCs and use it to define their directions.

Make your villain smart but not all seeing

An interesting villain is smart. He has his own goal and plans. While your PCs are moving the story forward, so is your villain. He doesn't make stupid mistakes or twirl his mustache and yell "curses!" Your villain should move forward with his own plans as the PC's move through their own.

It's easy to take this too far, though. A villain should be smart but that doesn't mean he is all-seeing. He doesn't know what is in the minds of your players. It's easy to let the villain know what you know, but he does not. Be sure that your villain only acts with the information clearly in his hands.

Understand how they justify their actions

Going back to Magneto in X-Men, the scene with his parents in the death camp does more than just define his background; it gives him something else, something crucial for any villain you want to make. It gives him justification and purpose. Based on that experience, Magneto believes his views and actions are right. He believes he knows what will happen if he does nothing; if he takes the high road like Xavier, the mutants will be lined up and shot. Magneto is a great villain because he believes he is the good guy.

What makes your villain think he or she is the hero?

Any of these tips can work for building a PC or building any NPC, villain or not. That's part of what makes an awesome villain; he's just a person like anyone else. The villains your players will remember are the ones with whom they could agree.

We love our stories. We wouldn't run D&D games if we didn't. We love the structure it gives us to build an interactive game and we love the freedom to make that game our own. It's easy, however, to fall into some common traps that might seem like good ideas but end up either boring or frustrating players.

Banish the God in the machine

A common phrase for one of the worst story pitfalls is deus ex machina, or "the God in the machine". Does some powerful being have more control over the story than the PCs do? Is there a major NPC that is guiding the path of the PCs? Has your party been rescued from certain death by an all-powerful force?

Your party should almost always use their own power and own decisions to guide the story. Their actions should dictate where things go or how they get out of a situation. No force, seen or unseen, should manipulate, save, or thwart your PCs without some action of their own moving the story forward.

Let the wits, skills, and deeds of the PCs drive the story.

Keep the PCs at the center of the story

Likewise, we may spend hours developing our background story and campaign world only to discover that the PCs have a very small part to play in it. This will be clear to them as they stumble through their own lives in this much bigger world. It's important to build a living world, but your PCs should always be the center of your story. The world acts and reacts to them, not the other way around.

Focus your story around your players. Don't bother building out a world they will never see. Build it out as they explore it. Stay a step or two in front of their actions, not miles outside of their point of view in all possible directions.

Resist prophetic outcomes

Avoid outcomes based on prophecy. Make the PCs the master of their own destiny. Don't spell out their destiny through prophecies, signs, and fortunes that describe what they will or won't do.

In general, ensure that your PCs feel in control of their world. Ensure that they feel like the center of their story. Relax your grip on the story. Let it grow as your PCs act. Make sure they feel like their actions have meaning. Ensure that your NPCs act and react to them. Don't make your PCs feel like small fish in a huge ocean. Make them the masters of that ocean.

Designing unique encounters is critical to keeping your game fresh. Sometimes a standard straight-forward battle is what you seek. Other times you need to throw every trap known to man at your group to keep the battle jumping.

Here's another checklist you can use to ensure you've considered all of the possible variables for designing a unique encounter:

Not every battle needs all of these items. This list, however, can make it easy for you to decide which elements make the most sense for the encounter you want to build. Using these variables, you have an unlimited number of options to make each encounter memorable.

Your job as a Dungeon Master is to keep your game as exciting as possible. For your most challenging encounters, you must keep the PCs as close to death as possible without actually killing them.

Think back to your favorite action movies, movies in which the heroes are constantly put on the edge of death only to fight their way to survival and triumph. That's a hard thing to maintain in your game week after week.

A good D&D game has peaks and valleys of challenge. For about half of the battles, the PCs should face challenging foes but not necessarily be pushed to their full limits. Making these battles fun when the actual challenge is low is tricky. Try adding interesting puzzles, story elements, and unique environments to keep these battles interesting.

For other encounters, such as key confrontations with an ultimate nemesis, the battle should be very challenging. It should require every ounce of resources the PCs can muster and every tactical advantage the players can grab. It should bring them to the brink of death without actually pushing them over the edge.

Keep the balance of challenge and fun always in your mind. When your players feel like they're walking through too easily, give them a dose of some pain. When they look haggard and pale from the constant stress of hanging on the edge of death, give them a break. Sometimes they just want to crush an army of minions. Other times they want to be hanging off of a cliff while a blue dragon stares them down. Keep an eye on them, learn to watch the reaction of your players, and be ready to give them what they want.

Building compelling battle maps is critical to keep the game fresh week after week. Here's an expansion of the encounter design checklist focused on the battle map itself:

Like the encounter checklist, you won't always use all of these elements, but reviewing the list might give you an idea for spicing up the battle you had in mind.

Build an interesting environment

Make the physical environment of the encounter interesting. Put in rubble and walls that might block line-of-sight. Make the walls crooked or broken down. Add furniture, signs of previous battles, pools of oil, or anything that might spark the players' interest. Add details wherever you can.

Write remarkable read-aloud text

Write text that describes the remarkable features of the environment. Don't simply describe how these details play out in battle. Describe the smell from the alchemy. Describe the terrible rituals written out in blood on the hanging flayed skin of the goblins' victims. Let their minds imagine the scene before you reveal the combat-focused details.

Include fantastic terrain

Add areas that might affect either side of the battle. Wizards of the Coast refers to this as Fantastic Terrain in the Dungeon Master's Guide. A river of lava, gaseous mushrooms, cursed altars, or many other pieces of terrain include game changing mechanics for those who step close or directly into them.

Add traps or hazards

Though they act a lot like monsters, static traps can change how players would expect a typical battle to play out.

Include player-focused environmental powers

Add elements the PCs can directly use as terrain effects. Add flaming flagons of dwarven mead they can toss, ancient arcane ballista they can fire, or boulders they can roll onto their foes. Any of these types of environmental powers can give your players a reason to break away from their standard combat tactics.

Let characters use minor actions to activate these powers and these powers will get used more often. Most players won't waste a standard action on the unknown, they will take a chance with only the loss of a minor action at stake.

Build interesting maps

There are a lot of different tools available to build battle maps. Some cost as little as $10 for a wet or dry-erase map. Others, like D&D Dungeon Tiles, will cost about $10 a pack with multiple packs required to build interesting layouts. High-end map accessories like Dwarven Forge can cost much more but offer highly detailed 3D battle maps.

The accessories themselves do not make a map interesting, however. For that you need to think outside of the components you own and consider how you can mix them together. For example, begin with a basic dry-erase battle map. Draw on the basic features of the terrain your players will encounter such as hills, trees or rubble. Use Dungeon Tiles to build out sections of a keep in the center of the map. Now, using blocks of wood, place dungeon tiles on top of the blocks to raise them above the platform.

http://newbiedm.com suggests using small wooden spools from the Michael's craft store to raise up platforms above your map.

A small pack of blue sticky tack helps you put together your battle map and get it to stay that way throughout your adventure.

Dwarven Forge can be very expensive ($130 a set), but you can also add it to your standard dry-erase maps and D&D dungeon tiles to build unique, detailed, and interesting battle areas.

Add special effects

Add special effects to your battle map to make each of your battle areas more exciting. Small tea lights and wedding chime lights from Michael's make for some exciting lighting effects. Check the wedding section and look for packs of tiny chrome lights at about $2 a pack.

Mix these lights with some fake spider webbing, usually available in any drug store or craft store in the months around Halloween. This spider webbing illuminates very well when paired up with LED and tea-lights to form smokey, fiery areas or illuminated portals.

Browsing through your local craft stores or costume and party stores can give you lots of ideas for elements to add to your game.

Steal ideas from everywhere

Like the rest of your adventure creation, when planning encounters, steal from everywhere. Whether it's from old books on medieval architecture, websites from other dungeon masters, or your niece's dollhouse, always keep your eyes open to new ideas and new ways to make your maps as exciting as possible.

All too often it becomes easy for DMs to think like the antagonist of the story. We spend a lot of time in the minds of our villains, plotting our attacks and designing our devices of destruction.

Unfortunately, this might take us away from the true mindset we need to have - making the game enjoyable for our players. A good piece of that enjoyment comes from the challenge we provide but it also comes from the situations that let them enjoy their characters.

When designing an encounter environment, it isn't enough to build terrain elements that challenge the party. You will also want to add in terrain elements that make the terrain enjoyable for players.

Putting a holy altar that adds +1d6 radiant damage per tier is one such example. Another is the blood of an elder primordial that allows any creature standing upon it to critically hit on rolls of 19 and 20. Players are sure to seek out such areas and prevent their enemies from using them as well.

More difficult are terrain elements that your players will enjoy but without a clear benefit. Perhaps the ranger in your group prefers to climb up to high platforms to avoid dangerous melee opponents. Maybe your glaive-wielding fighter likes wide open spaces. Maybe your rogue likes areas of deep shadow.

These indirect methods can be ultimately more rewarding. Your players aren't sure you designed it just for them - they think they found a way to use the terrain that you didn't plan. Keep an eye and an ear out for the terrain your group enjoys the most.

Above all, remember that the encounter environment you build is for the fun of your players. Sometimes that means a real challenge, but other times it should mean they get to use the environment for their own, sometimes unexpected, benefit.

At the heroic tier, minions behave as expected. Five or six minions in a battle will do what we expect them to do. They'll harass the PCs. They'll get in a bit of damage and offer combat advantage to some of their foes. Then they'll die fast.

At the paragon and epic levels, however, it becomes too easy to kill minions when they are simply used as a horde of bad guys. PCs at level 11 and above often have ways to automatically inflict damage through area effect powers, stances, and auras. Effectively using minions at levels above 10 requires some thought on behalf of the DM. Here are a few ways to effectively use minions above level 10.

Bring them out in small groups

When your PCs have many ways to kill large groups of minions at will, bring your minions out in small groups. Bringing out four minions at a time, two or three times in a battle keeps the impression of a large horde coming in without all of the minions dying in the first round. Bring them in through a few different entrances. Have them spread out so only a handful get killed by large area attacks.

Build minion spawning mechanics

In larger battles, build in minion spawning mechanics such as teleportation portals or elite and solo creatures able to spawn minions directly. You can then build skill challenges into these minion spawners so that players can disable them to get rid of the flood of minions.

Give them a free round of attacks

When you have minions enter the stage, give them a free round of attacks before the party has a chance to wipe them out. Don't have them actually enter the battle until it's their turn; then give them their shot at harassing the party before they're killed. The same is true for the minion spawners. The minions should get a turn right after they are spawned.

Optimize the minions' actions

It's easy to forget how many actions your minions get to use. Consider six minions for the cost of a standard monster at level 21. These six minions may only have one hit point but each of them has a standard, move, and minor action every round. That's 18 actions to the single monster's 3 actions. Figuring out how to maximize the use of all of those actions can make minions extremely versatile in a fight. If your encounter has effects triggered by minor actions, minions can conduct those minor actions easily. Standard actions like Aid Another or Heal can make them more effective when paired up with more powerful elites or solos who have one particularly devastating attack to perform. When planning out a battle with a lot of minions, consider how you will effectively use all of these possible actions.

Adjust minion damage

With the Dungeon Master's Guide 2, standard minion damage has been increased. Keep the chart of minion damage per level handy and ensure that your minions deal the proper amount of damage.

Adjust minion experience budgets

At paragon and heroic tier, experience budgets for minions don't make a lot of sense. Five or six minions are not worth the cost of one normal creature in most battles. Instead, add one creature of experience for every 10 to 12 minions and adjust based on how easily they are killed. More difficult situations involving minions might increase the experience budget. In general you will have to judge how many minions were worth the cost of a single standard monster based on how quickly they were killed.

Don't forget about why players love minions

Most of all, don't forget that minions are the seasoning in a recipe. They aren't designed to be a powerful threat. They're meant to be killed by the dozens. Ignore the rules above every so often so that your players get to enjoy tearing great piles of minions to shreds. Go ahead and have some of them run into a blade barrier or poison cloud. Always remember the role that minions are supposed to play in your game before you work too hard making them difficult to handle.

Solo creatures are often the powerhouse monsters our PCs will battle throughout their adventure. Acting as your party's greatest foes, a solo creature is designed to challenge an entire party of adventures. Unfortunately, many do not.

Here are a few reasons for this imbalance. The main one is that even though a solo has the toughness and firepower of a group of five monsters, it is still a single monster. While many solo monsters have more actions per turn, none of them have as many actions as a full group of five monsters. Solo monsters simply don't do as much in a round of combat as a group of five adventurers.

The second major problem with solos is their weakness to status effects. Any effect that hits a solo is the equivalent of hitting five normal monsters. That single target stun the PC might have is five times more effective against a solo creature than it is against a group of five monsters.

Luckily, you can get around these problems with a couple of simple house rules.

Status effect protection

First, consider adding some form of status effect protection to your solo monster. One option is to reduce the effectiveness of stuns and dazes with the following house rule:

When stunned, this creature instead loses its next standard action and grants combat advantage. When dazed, this creature instead loses its next minor action and grants combat advantage.

This is a good solution for two reasons. First, the over-effectiveness of dazes and stuns is reduced. Second, we didn't actually remove the usefulness of powers that stun or daze. Dazing and stunning powers are now reduced to only slightly more useful than they would be against a group of five monsters. You don't want to take away too much from your players when trying to balance something. You want to ensure that their effectiveness is still there only now it is in line with the intent. In short, don't remove something - reduce it.

Environment integration

In a series of articles, http://at-will.omnivangelist.net/ describes a concept he refers to as Worldbreakers. These high-powered solo monsters often fully integrate with the environment in which they do battle. Because of the high integration with their environment, you will often not find published monsters that fit this concept.

At various stages in the fight, these solo creatures will change the environment in which they fight. A red dragon may create pools of lava around its lair. A giant may smash into walls, sending stalactites raining on top of the party. A wounded spider lord might summon hordes of spider swarm minions from four mounds around the battle area.

These effects keep encounters against solos interesting all throughout the battle. Beating down a creature with five times the hit points of a normal monster might get tedious, but these changes to the environment alter the entire battle and the strategy the players have to take.

Environmental integration also improves the solo creature's lack of actions. Map-changing effects that happen at set times in the battle do not reduce the solo creature's actual effectiveness.

More Damage

In general, solo creatures above level 10 don't do enough damage. To fix this, try adding +5 damage at the paragon tier and +10 damage at the epic tier. This will let you run a solo that threatens the party without having to add more creatures to keep the damage up. Another option is to use the Damage Per Level chart in the Dungeon Master's Guide 2, find the appropriate level and use the high damage amounts for at-will and limited attacks instead of the monster's defaults.

How not to improve your solo creatures

When tweaking your solo monsters avoid any effects that heal the solo. Be careful when using too many effects that reduce the damage output of the PCs. Battles against solos already take a long time. When dazed or stunned or blinded, the damage output of the PCs drops a lot. Before you add effects like this, be aware they may simply make the battle longer instead of increasing threat.

Solo monsters should be challenging and dangerous but not frustrating. Your players should feel threatened but should walk away from the battle having enjoyed the experience. As you tweak your solos, keep your goals in mind.

A standard battle in D&D 4th Edition should take about 45 to 60 minutes, but a big battle with more than five players may very well last 2 hours. You can either speed up combat using rules-as-written or some simple house rules.

The one rule of fast combat - do more damage and take more damage

Battles all come down to the amount of damage dealt. Anything that gets in the way of a creature or player dealing damage will slow combat. If you want to speed up combat, deal high damage to your PCs and ensure they can deal high damage back to the monsters.

Understand your creatures

Spend some time understanding and recognizing which creatures will slow down a battle and which will not. In general, soldiers and controllers run slower than brutes, skirmishers, and artillery. Creatures higher level than the PCs will take longer to kill than creatures equal to or lower than the level of the PCs. Take note of each creature's possible status effects. Many status effects hinder the PC's ability to do damage. Examples include stun, daze, blind, immobilize, slow, and higher-than-average defenses. If you want faster battles, replace these status effects with inflicted vulnerabilities, reduced defenses, or ongoing damage.

Add an "Out"

As described earlier, add an "out" as part of your encounter design. Come up with a way for the battle to end that isn't necessarily the complete elimination of one set of combatants. Make sure this is something your players can easily discover.

For example, your party is facing off against an evil wizard who is attempting to summon a powerful demon. During the battle, the party must interrupt the wizard's spell either by defacing his summoning circle or disrupting the casting. Even though the wizard has many protectors, the real goal of the battle is to either kill the wizard or destroy the summoning circle. When either case is met, the remaining combatants turn to ash.

Sometimes the "out" may be too quick, so be prepared to ensure that enough conditions are met to make it a challenge. Perhaps the wizard in the example has shield golems that take on 50% of the damage dealt to the wizard.

The Out is a great way to keep your combat short and to make each battle unique.

Add damaging terrain

Fantastic Terrain that inflicts damage is a great way to keep a battle running fast and still keep the threat on the players high. Large sections of an encounter map that do damage, such as 5 damage per tier to any who enter or begin in the area, will put out significant extra damage to both sides of a fight. If you choose this option, be sure to include creatures or encounter effects that can move PCs into the damaging areas or else it will only hit your monsters.

Hopefully these tips will help you to keep your battles running fast and furious.

Most of the time, encounters should be built around the story you want to tell. They should be designed to fit the theme you have in mind and then built to entertain your group. Sometimes, however, you want to really challenge your players. You want to give them a battle that reminds them how dangerous the world is. This is when you want to optimize your monsters - finding the perfect mix of monsters to bring the pain down on adventurers whose egos could use readjustment.

Combat advantage and sneak attack

The easiest way to optimize a group of monsters is to mix monsters that inflict extra damage on combat advantage with monsters who inflict status effects that grant combat advantage. One example is the combination of Grells and Quicklings. The Grell's dazing attack provides the Quickling with the combat advantage it needs to inflict extra damage. Any combination of dazing, blinding, restraining, or prone knocking creatures with creatures that inflict extra damage with combat advantage can be very effective.

Status effect producers and users

Other monster combinations that work quite well are creatures that produce a status effect and creatures who gain an advantage, usually extra damage, against creatures inflicted with that status effect. For example, the Deathlock Wight has a power that immobilizes its target. The ghoul gains extra damage when it strikes immobilized targets. Mixing the two creatures together can be lethal.

Resistance negaters and elemental attackers

At higher levels, PCs are very likely to have resistances to elemental effects. If you have a particular battle focusing on an element the PCs resist, it might be quite an easy battle for them. To optimize an encounter, include creatures that negate resistances with those that inflict an attack with that elemental type. For example, the Immolith can draw creatures into its aura, negating any resistance to fire. Inferno bats are then free to inflict fire damage on these creatures. Other creatures that negate necrotic resistance mix well with those that inflict necrotic attacks.

Monster and environment optimization

Optimizations don't have to focus only on monsters. Mixing monsters with the right environment can likewise put the pinch on your PCs. The above-mentioned Immolith sitting in a pool of fiery lava will inflict even more damage than just its attacks. Acidic pools mixed with immobilizing creatures or creatures that can knock PCs prone can keep PCs stuck and burning for some time. Finding the right mix of environmental effects and monster powers can be effective at giving the PCs a real challenge.

Don't get carried away, however. Your job as a DM isn't to defeat your players and kill their PCs. Your goal is to give your players a sense of danger and a thrill of victory. Players enjoy resisting damage most of the time. Don't take it away too often. Use these optimizations when doing so would bring the excitement your players desire, not when you're pissed that they drank all your Mountain Dew.

It's just as easy to build a bad adventure as it is to build a good one. Below are two pitfalls to avoid when designing an encounter.

Harsh terrain

Fantastic terrain adds flavor to your battles, but it has different properties and effects than those from a creature, trap, or hazard. Because terrain features take place most often when a creature enters or begins within the terrain, you will want to avoid using terrain that inflicts any ongoing status effect that might make it too hard to get back out again. Such effects include stuns, dazes, immobilizes, or being knocked prone. These effects may make the area too sticky, making it too hard for a creature to ever get back out once they enter.

For example, a patch of slippery slime might inflict 5 poison damage when a creature enters or begins within the slime. If that slime were to also immobilize (save ends), a creature that enters those squares might never be able to get out again. Because creatures normally save at the end of their turns, they will rarely have a chance to rid themselves of the effect that keeps them there. It just hits them again and again.

When designing terrain, ensure that there is a way for creatures to get out once they get pushed in.

Bad combinations of effects

Like terrain, the wrong combination of status effects can slow a game to a crawl. Such combinations include multiple dazing creatures, multiple stunning creatures or creatures that stun too often, creatures that weaken and also have the insubstantial quality, or creatures with sustainable blinding or darkness powers.

You will want to avoid using too many creatures with these qualities all at once. Sometimes, though, you might not find out until it's too late. If that is the case, don't overuse these qualities within the battle.

For example, if you're running a black dragon, you will not want the dragon to stay within its own darkness cloud indefinitely. Though doing so gives it a clear advantage in battle, it also makes it so much harder to fight that your players are likely to become bored.

The same is also true for the standard dracolich. The dracolich has so many different ways to stun PCs that players are likely to get stunned again and again. Spread out the stuns to ensure no one PC gets stunned over and over or institute a house rule that turns the dracolich's stun into some other sort of debilitating effect such as ongoing necrotic and cold damage.

When you're designing a battle, pay particular attention to the effects of your creatures and your terrain. Space out any debilitating effects appropriately so they do not slow your game to a crawl.

A good adventure runs like a stage show, with dozens of intermixed elements to make each game special and exciting. Adding props and handouts to your game is one such way to keep your players busy and interested.

Build and hand out notes and letters

The easiest prop to make is the old letter or note. Here are a few ways to make a sheet of paper look old. Soak a sheet of paper in coffee for a few hours to make it look like aged parchment. Office supply stores like Staples also carry parchment paper that has a great aged look.

Using your favorite word processor, find the fonts that best correspond to a fantasy environment. For more authenticity, choose a font that corresponds to a particular villain who might be leaving notes behind. This font can represent the villain's own handwriting. A small piece of clip-art either embossed in the background or at the bottom can act as a signature. A dash of red paint on your notes might add a realistic blood splash on the page as well.

These notes are a great way to keep your players moving in the right direction, providing them with clues to events that they may not have participated in themselves. Whether they're spy notes given directly to the party or notes captured from fallen foes, these pieces of the puzzle can help fill out your game world piece by piece.

Add puzzles

You might also add puzzles to these notes. For example, use a basic Caesar cypher to encrypt the message the party has captured. A Caesar cypher replaces each letter of a word or sentence with a letter a certain number of characters ahead or behind. For example, the word dragon pushed seven characters forward would be kyhnvu. The party can crack the cypher themselves by sorting out the most common words and letters. It's hard to decode a single word but a long sentence or paragraph with some common words like a and the make it easier. For more, read about Caesar cyphers on Wikipedia at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caesar_cipher.

Other props

Try adding other physical props to your game as well. Old plastic skulls purchased from a party store during Halloween, fake costume jewelry, and old coins can give your players a physical sense of the materials they might find in game. When there is a major plot-related item in your game, consider trying to find an actual physical representation of that item to hand out to your players.

The best places to find physical props are at old antique stores, costume stores, craft stores, and party stores. Try shopping shortly after Halloween to find these items on sale.

Like every element of a good D&D adventure, keep your eyes and your mind open. Props are out there waiting for you to grab them up. You just have to see them.

From time to time you will find yourself with a table full of players mostly staring at their smartphones or laptops while one player decides what to do. Consider your reaction to this carefully. You might think about banning electronics at your table or swatting their bluetooth headset out of their ears with a copy of your NPC baby name book. Instead, ask yourself if the electronics are to blame or are you simply not grabbing enough of their attention at the table? Instead of banning electronics, find ways to return their attention to the game.

Run two at a time

When a battle goes slowly, have two players run their turns at the same time. Have players pre-roll their attacks and damage to keep them focused on the battle rather than playing Plants vs. Zombies between rounds.

Ask for off-turn skill checks

Ask players to perform skill checks like history, nature, religion, perception, insight, and dungeoneering off of their turn to observe some detail of the encounter they haven't yet uncovered. Let players perform insight checks on their foes off of their turn while someone else is going through their round. When you see a player drifting away from the game, draw them back by asking them to roll a skill check and reveal a bit of information the group didn't have before.

Use the buddy system

Before the game begins, assign each player a buddy with whom they can discuss tactics. When one of these players begins to drift, the other can bring them back to the game by discussing their plans. Off-turn table strategy between two players takes far less time than a full table of players discussing strategies during the current round.

When creating the buddy system, consider carefully who goes with whom. Do the classes of the buddies fit well such as a defender and a leader? What about the personality types of the players? Two strategy-oriented players may not work as well as a strategic player and a kill-focused player. Make sure the personalities you put together in your buddy system make sense.

Assign a rules lawyer

Do you hear complaints about the rules lawyer at your gaming table? This player constantly quotes page and subsection on any possible question that comes up during the game. A designated rules lawyer, however, can be a great benefit as long as he or she remain objective. Be careful of the rules lawyer who constantly finds loopholes to support his or her own agenda.

An objective designated rules lawyer will spend more time paying attention to the game and will help other players figure out their possible options. The result is more attention spent on the game at hand and less updating Facebook or sending tweets.

Keeping all of your players in the game can be a difficult thing to do. Don't beat yourself up if you see them drifting and don't chastise them for it either. Instead of yelling about how Blackberries are destroying cohesive thought, find ways to draw them back into the game. Make it interesting for them to return and they will indeed return.

One of the hardest jobs you have as a DM is managing the time at your table. Like a three-act play, a three-hour movie, or even a haiku; you have a structure to your game and you have to manage the game to fit within that structure. While you might break this structure down into a number of encounters, roleplaying events, or skill challenges, you also have to break it down into the time allotted for your game. Running three encounters in four hours requires careful preparation and table management. Here are a few tips to help you manage time at your table.

Prepare well

Preparing well is the first step towards running a smooth timely game. Make sure all of the required components are ready, not just for the game but for your guests as well. Have a plan for food. Have drinks on hand. Make sure your guests know to arrive on time and are ready to play. The better prepared you are, the more likely the game will run on time.

Monitor pace

Begin speeding up your game during the very first encounter, not the last. Pay attention to the pace of your game early on and begin to steer things in the right direction. If you see a player who needs help, assign that help early. Don't wait until the last battle to add in techniques to speed up the fight.

If you can, keep a timer handy and monitor the pace of a battle. Look for and understand the reasons your battles take so long and adjust as soon as you are able. The sooner you get the proper changes in place to speed up your game, the better the rest of your game will run.

Name who's on deck

Instead of only telling a player when it's his or her turn, tell the next two people in a row. Tell one person they are up and the next person they are on deck. Make it a habit and ask your players to remind you to ask in case you forget. With a player on deck, each player should be prepared to act rather than making decisions at the last minute.

Show initiative, delegate, and keep it moving

Whatever initiative system you choose, choose one that lets all of your players see it. The folded card over the Dungeon Master's screen works well for some groups. 3x5 folded tent cards or names on a whiteboard can work equally well. Assign one of your players the job to push initiative forward, yet keep an eye on it yourself. This serves the purpose of bringing that player's attention to the game as well as assisting you in managing turns.

Shut down arguments

Few situations waste time and suck out energy more than arguments. Often arguments are between a DM and a player on a rules question but other times it's player vs. player. When in any sort of doubt, make a good judgement not fueled by your feelings, and move on. If you have assigned a rules-lawyer, consult him or her and pass judgement. The key is to judge quickly and move on. The softer you shut down the argument, the better the player will feel when it occurs, but a judgement must be made to keep the game moving smoothly.

If an argument occurs between two players, stop it quickly. Tell them they can discuss it off of their turn but move the turn along. The more heated it is, the quicker you will have to step in before egos take hold and the argument becomes more about who is right than a disagreement over the topic itself.

Arguments at the table can steal a lot of time from the game and make the game less fun to play. If a problem persists with a particular player or players, take them aside outside of the game and talk about it. Ask them what they want and what is getting in the way. Look for the source of the problem below the surface, not just what is on the outside. The sooner you can fix the source of an argument, the better your game will be.

Try to bring everything back to the story. When you adjudicate a rule, explain how it works within the story, not just the mechanic of the rules. Seek every opportunity to bring things back to the story you are all telling.

Always be rolling

Put that coffee down. Get the dice in their hands and get them rolling. When running best, a round of combat in D&D should be action after action, roll after roll. Talk to your players about preparing their actions and decisions before their turns begin so they are ready to move the mini and throw the dice the second their name is called. Sometimes you will want to start someone's round earlier than the end of the previous. There's nothing wrong with having two people perform their rounds simultaneously if they can do so without messing up the other player's actions. Even if a contradiction does occur, it's usually easy to fix.

If you want to speed your game up even more, have players pre-roll attacks and damage before their turn. When their turn comes up, they tell you their resulting attack and damage rolls.

Always keep an eye on the pace of your battles and ensure that dice are always rolling on the table.

Keep it fun

Don't go overboard trying to keep the pace going. Players don't want to be rushed and doing so might make your game more stressful and less fun. If players are running slow, work with them to speed things up, but don't push too hard. Everyone's there to enjoy themselves, tell stories, and joke with each other. Don't take that away. Instead, ensure the current player is moving along while everyone else is enjoying themselves.

Find the right techniques that work for your group to keep your game running smoothly and keep your players having fun.

Of all of the elements of D&D 4th Edition, none is more controversial or misunderstood than the skill challenge. Two years into the game, many of us, myself included, don't exactly know the best way to run a skill challenge. Here are a few basic tips to help you run fun skill challenges.

Keep them short

Instead of a single large skill challenge, break your skill challenge up into a series of smaller skill challenges. Replace a giant "explore the city" challenge with a few challenges built around certain specific locations or people with whom the PCs might interact.

Keep them focused

Ensure that your skill challenges have a clear goal. Skill challenges can become muddy and unclear if players don't know exactly what is happening or what they should be doing. Make sure the goal of the challenge is clear and the situation is well understood.

Think it through

It is likewise important to fully understand the challenge you are going to give your players. Think of the challenge as a real situation, not a set of game mechanics. Consider what the PCs will actually be doing. If the party has to disarm a large trap, understand and explain how the trap works.

The more details you can give to your players about a challenge, the more likely they are to understand it and enjoy the challenge.

Don't let them know it's a skill challenge

Instead of stating clearly that they are in a challenge, try mixing the challenge with the story you are telling them. Keep track of successes and failures behind the screen and alter the path as they travel through the challenge. This removes some of the game mechanics from the view of the players and instead keeps them focused on the story.

Make the goals, rewards, and penalties clear

Although you might want to keep the fact that the players are in a challenge to yourself, make the purpose of the challenge clear. Tell them what rewards they may gain by succeeding and what penalties they will face if they fail. Keep these criteria in mind as you design the challenge and ensure that it is equally clear to your players when running the challenge.

How your group responds to your skill challenges will vary greatly from group to group. Some groups love the intricate stories and chances to roleplay that they can find in skill challenges. Other groups simply want to crack goblin heads together. Stay flexible and get a good understanding of your group and their desires. Then build your challenges around what they enjoy the most.

Some of your players may love falling into their characters. They keep a vault of characters in their heads just waiting to be freed. They come up with pages of background stories, complex personalities, and draw up flow charts of exactly how their characters will act in any given situation.

Others, however, aren't as easily drawn into roleplaying. Maybe it's growing up with console and computer games. Maybe it's the sheer amount of characters in fiction to which we are exposed in the rest of our lives. Maybe we've just grown out of it as we did playing He-Man and running around the back yard pretending we were superheroes.

However, as the dungeon master, you can help draw people back into their character. Help your players see through the eyes of their characters with the following tips.

Start with background and desires

Ask each of your players two fundamental questions: Where did they come from and what do they want? The answers could fill either a novel or a sticky note. These fundamental concepts create both trajectory and motivation. Starting with these two questions helps everyone get a better understanding of this character in just a few words.

Find out their deepest secret

What is this character's deepest secret? What is the one thing this character may never admit to the rest of the party? What secret defines who they are? This question exposes flaws in a character and helps your players stay in the mind of the character as he or she makes decisions knowing the one thing none of the other players know.

This secret also generates ideas for character-focused quests later in a campaign. Like background and desires, a secret can be articulated with just a couple of sentences.

Uncover their fictional archetype

Ask your players to choose a character from popular fiction who best represents their own character. This might be anyone from a movie, TV show, or book. Perhaps it's a fantasy character or a character from an entirely different genre. This also works very well for DMs who need a quick NPC and want to give it some realism. Quickly deciding that your evil NPC wizard is like Walter White in Breaking Bad - a man who wanted to provide for his family but did so by changing from school teacher to drug manufacturer - immediately tells you who this character is and maybe even what he looks like.

Use the character's name

Once your game is in progress, use the character's name on your initiative board and when you call out the next turn. Avoiding real-life names helps your players get into their characters instead of simply thinking of their characters as a sheet of paper and a miniature.

Be careful not to push too hard to get your players to roleplay. If they're not into it, you want to relax and let them play the game however they want. Gauge your players' interest and show them more of this game than they might have expected. The commitment is low, the risk is low, and the outcome might be something really great.

Dungeons & Dragons is a complicated game. If you use a lot of accessories you could end up spending quite a bit of money. This doesn't always have to be the case, however. Here are three tools you can use at your table that cost next to nothing and make the game easier and more fun to play.

Bottle rings

Use the tiny rings that sit under the cap of most soda bottles to keep track of status effects such as bloodied, marked, cursed, or quarried. You can grab up these little rings for free from empty soda and juice bottles. Drop them over any miniature to apply a status effect. A handful of these rings can go a long way to keep your game moving along and keep all of your players aware of the various conditions.

Pipe cleaners

Multi-colored pipe cleaners are useful for marking the zone of any ongoing area effects. You can bend them to just about any shape and expand them by twisting two pipe cleaners together. If you don't have bottle rings, use some cut up colored pipe cleaners as status markers to drape over miniatures.

Index cards

Build a simple and effective initiative system with a few strips of index cards. Cut these cards into strips and fold them in half. On the bottom edge of both outside edges of the card, write the name of each PC. Write up a few cards for your monsters as well labeled Monster 1, Monster 2 and so on. Drape these over a Dungeon Master screen so you and the players can all see what the initiative order is. This will speed up the game and keep players engaged.

You can purchase many other useful DM aids on the cheap. Take a walk around your local office supply store and see what sort of stuff you can pick up to keep your own game organized and fun to play.

Sometimes the rules-as-written don't give you the tools you need to make the game as fun as you can. Other times you will want to add something to bring a different dimension to the game. Luckily, D&D 4th Edition is a flexible system with lots of room for house rules.

Run house rules behind the screen

Whenever you can, keep your house rules behind the Dungeon Master's screen. If you feel like defenses, attacks, or damage aren't high enough, make the modifications to your monsters, not to the PCs. This way you can tweak them as much as you want without changing the rules every week. Further, many players use the D&D Character Builder and would have a hard time customizing it to fit in any house rules you have created.

Keep your house rules behind the screen to make it easier to add, modify, and remove house rules as you see fit.

Add an extra challenge

At the paragon and epic tiers, the challenge monsters impose may not be as strong as it was in the heroic tier. With the sheer number of ways PCs mitigate and heal damage, you might want to give your monsters an extra boost of damage. WOTC designer, Greg Bilsland recommends doubling a monster's static damage bonus to increase their damage output. For brutes, try tripling the damage bonus. Doing so will keep the threat high and ensure your PCs wont simply walk through encounters they should have found more challenging.

Give PCs a theme song

This house rule I also heard from Greg Bilsland. Have players pick a song they think fits their character. Add this song to a long playlist of music that you play during the game. Whenever that PC's theme song comes up, he or she jumps to the next spot in the initiative, gains one extra standard action, and increases his or her critical threat range by 1 (a crit on 20 becomes a crit on 19 or 20).

This rule adds an element of cinematic action to your game without changing the balance too much or making the game any harder to play.

Above all, add in house rules when it makes the game easier and more entertaining. Avoid complexity and always have a really good reason to add new rules to the game.

D&D has changed much over the past 40 years, but no change has been greater than the internet's ability to bring together the greatest dungeon masters in the world. What once was a mystery locked within a red box is now open to all of us to explore and understand together.

Use this D&D hive mind to your advantage. Learn what we all have to offer. Spend time with the circle of D&D fans on message forums, weblogs, and social network sites.

In particular, you can find a great wealth of minds focused on Dungeons & Dragons on Twitter. Many of the game's designers, developers, and top bloggers spend time on Twitter discussing every product and every topic you can imagine.

You can find these D&D designers and bloggers on Twitter at the following URL: http://twitter.com/SlyFlourish/dnd4e

Second, visit the forums of Enworld at http://enworld.org. This is one of the most active and mature forums for Dungeons & Dragons. It maintains general discussion, rules discussion, and house rules forums.

With these two resources at your disposal, you have access to far more knowledge about D&D than ever before in the history of the game. Use it to find useful tips and tricks to improve your game.

This book would not have been possible without the help and guidance of many people. I have learned more about running a Dungeons & Dragons game over the past 2 years than I have in the rest of my life before it.

The tips you find in this book came from many sources and I would like to thank as many of those responsible as possible.

I would first like to thank the Wizards of the Coast Dungeons & Dragons team that have made themselves available on Twitter. They have shown how integrated a company can be with their fans. This includes:

wizards_dnd.

Second, I want to thank the following people on Twitter who have have become friends of mine and proved that I am not alone in my obsession for this hobby:

tychobrahe

I want to thank my wife, Michelle, who participated in every D&D game I've run in the last decade and edited this book. I want to thank my friend Marilyn, who edited this book though she finds the topic of Dungeons & Dragons as exciting as a book on the history of the Twilight saga. She is the smooth channel between my ideas and your mind.

I want to thank Jared von Hindman for the art on the cover and within this book. He is the most creative artist I have ever had the honor to know and I hope you've enjoyed his art in this book as much as I did. You can find more of Jared's art at http://twitter.com/jaredvonhindman.

Lastly, I would like to thank you, the reader of this book, who spent the time to read it and the money to buy it. I hope you found it useful and will continue to find it useful in the future.

Thank you,

Michael Erik Shea

July 2010

Chalker, D. (2 June 2009). The 5x5 Method. Criticalhits.com. Retrieved from http://critical-hits.com/2009/06/02/the-5x5-method/

Holkins, J., & Krahulik, M. Penny Arcande: The Series Retrieved from http://www.penny-arcade.com/patv/

King, S. (1 July 2002). On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft. Pocket.

Mearls. M. (15 September 2009). Dungeons & Dragons 4th Edition: Dungeon Master's Guide 2 Wizards of the Coast.

Morrissey, R. En World Retrieved from http://www.enworld.org/

Murphy, Q. (30 April 2010). Solo Acts: The Worldbreaker At-Will. Retrieved from http://at-will.omnivangelist.net/2010/04/1511/

Orwell, G. (1946). Politics and the English Language Retrieved from http://www.mtholyoke.edu/acad/intrel/orwell46.htm

Singer, B. (2000). X-Men [Motion Picture]. USA: Twentieth Century Fox.

Tharp, T. (27 December 2005). The Creative Habit: Learn It and Use It for Life Simon & Schuster.

Wyatt, J. (6 June 2008). Dungeons & Dragons 4th Edition: Dungeon Master's Guide Wizards of the Coast.

Michael E. Shea is a writer, technologist, and webmaster born in Chicago, IL. Mike has played Dungeons & Dragons since 2nd edition in the 1980s and continues to play D&D weekly at his home. Mike is the creator and writer for http://twitter.com/slyflourish.

Mike lives in Vienna, Virginia with his wife, Michelle, and his fiendish dire-worg, Jebu.

About the Artist

Jared von Hindman is an artist and sometime comedian who "dug too deep" while researching Stupid Monsters of Dungeons & Dragons. He awoke something Dire and horrible (perhaps Fiendish, even) and now he spends his days playing with plastic elves and illustrating new and creative ways to kill goblins. Currently he resides in Berlin with an older woman and a snake named Slinky. He's not sure why his pet needs to be included in his bio, but all the cool kids seem to be doing it and Jared's a sucker for peer pressure.