New to Sly Flourish? Start Here or subscribe to the newsletter.

Dungeon World Fronts in D&D

by Mike on 11 March 2013

"Dungeon World's concept of fronts improved my D&D games immeasurably."

The power of the internet and the independent backing movement of Kickstarter has led us to a host of new and interesting RPGs. One of these in particular, Dungeon World, received a lot of attention, including the 2012 Golden Geek Game of the Year award. Built from the foundations of Apocalypse World and the roots of old-school D&D, Dungeon World builds a narrative-focused game based on conversations between players and game masters.

Dungeon World's story-building concepts fit well with the ideas of the Lazy Dungeon Master. Dungeon World games grow from the improvised conversations of players and game masters and the interactions of PCs with the rest of the game world.

One particular element of Dungeon World, the "front", has a very interesting effect on campaign building. According to Dungeon World, a front is a collection of linked dangers. Think of it as a sinister campaign moving along in parallel to the actions of the PCs. Larger threat than a typical encounter, fronts encapsulate a series of threats into a single package.

The Dungeon World "front" gives you a new tool #dnd adventure preparation.

Dungeon World relies heavily on the idea of "draw maps, leave blanks". These fronts don't build out entire story arcs; they simply capture a large moving threat that will, potentially, envelop the PCs.

Fronts consist of a set of dangers, each one representing a faction or a challenge tied to the front. Dangers include many components you might be used to such as a band of orcs, a thieves' guild, or a necromancer summoning a powerful beast. These dangers contain the following components that bring them to life:

- The Impulse: The motivation that drives this collection of villainy forward.

- Grim Portents: The steps this threat follows when unchecked by the PCs.

- The Impending Doom: The conclusion should this threat not be stopped or thwarted.

Let's look at a couple of the concepts of the front and how they might work in our D&D game.

The Impulse

Each front has a single guiding force, a motivation, known as an impulse. The impulse encapsulates the motivation that moves a front forward. Think of the nine ringwraiths hunting down the One Ring in Lord of the Rings. Their motivation is very simple; recover the ring and kill whoever has it.

This impulse should be specific and direct; nothing fancy or convoluted. "Become the God of Death" might be the impulse for a front based on Orcus's conquest for Godhood.

Each front moves forward, whether the PCs get involved or not. PC involvement may sway, redirect, or even stop a front. If the PCs choose NOT to get involved, that front moves forward anyway.

Grim Portents

Grim portents represent the steps a front or danger follows as it moves forward. In the original Apocalypse World roleplaying game, these grim portents are called the countdown — an apt title. Whatever this threat is, it moves forward. Things happen while the PCs go about their task. If they face more than one potential front and choose to follow through with another, the front they do not choose moves on to its inevitable conclusion. In Apocalypse World, a clock represents the countdown, broken out into quarter hours for the first three segments and five minute segments for the final three. This representation reminds us of the urgent nature a front represents.

Grim portents make the world come alive. There are no monster closets in our D&D games, no static bosses sitting on thrones of bone just waiting for the PCs to show up. Things are in motion towards their impending doom.

Impending Doom

If our band of heroes fails to prevent the front, the front concludes with an impending doom — the dark conclusion of the front or danger. Generally speaking, the impending doom shouldn't be a world-ending event or you force your players to choose it. Impending dooms should be sinister enough to get your players' attention but not so dire that they have no other choice but tackle it.

Structure Without Railroading

The format for fronts gives you just enough structure to help you form an idea of what is going on in the world without so much structure that you force-feed your story to your players. As Dungeon World and Apocalypse World state, we should draw maps and leave blanks. The blanks you leave give you and your players the freedom to fill in aspects of the story not yet defined. It gives you room to improvise during the game, building the story around the actions of your players, a story far more fantastic than any you might have written ahead of time.

Fronts are a great focused tool to build just enough structure to run a game without so much that you steal control away from the story that unfolds at your table.

Related Articles

- Looking Back on Dungeon World Fronts

- Custom Fronts of Storm King's Thunder

- DM Deep Dive with Adam Koebel on Dungeon World

Share this article using this link: https://slyflourish.com/fronts_in_dnd.html

Subscribe to Sly Flourish

Subscribe to the weekly Sly Flourish newsletter and receive a free adventure generator PDF!

More from Sly Flourish

Sly Flourish's Books

- City of Arches

- Return of the Lazy Dungeon Master

- Lazy DM's Companion

- Lazy DM's Workbook

- Forge of Foes

- Fantastic Lairs

- Ruins of the Grendleroot

- Fantastic Adventures

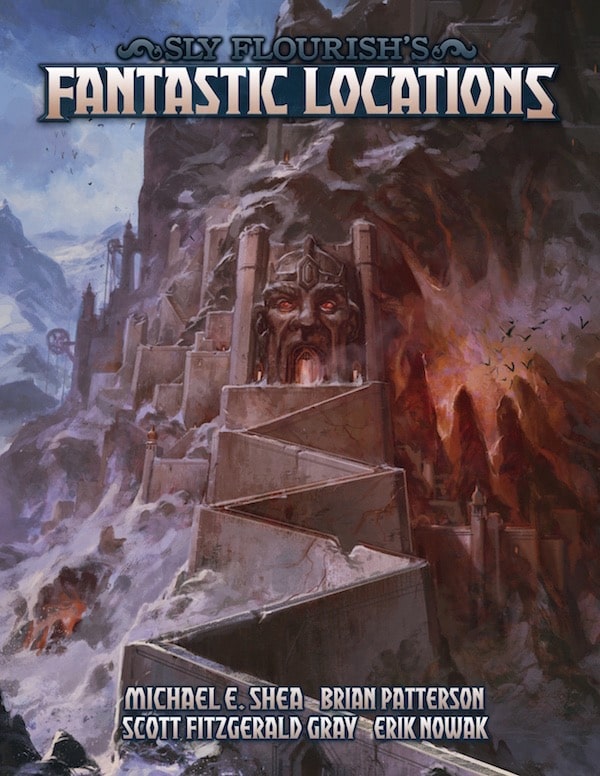

- Fantastic Locations

Have a question or want to contact me? Check out Sly Flourish's Frequently Asked Questions.

This work is released under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International license. It allows reusers to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the material in any medium or format, for noncommercial purposes only by including the following statement in the new work:

This work includes material taken from SlyFlourish.com by Michael E. Shea available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International license.

This site may use affiliate links to Amazon and DriveThruRPG. Thanks for your support!