New to Sly Flourish? Start Here or subscribe to the newsletter.

Playing D&D Anywhere

by Mike on 19 September 2016

RPG superstar Monte Cook has a new game he's working on called Invisible Sun. A big part of the game is the recognition that it's hard for players to all gather around the table to play an RPG during our busy lives. This is a great concept and it's one we can ponder and consider for other RPGs like our own favorite, Dungeons & Dragons.

How can we play D&D anywhere? How can two players play it without a DM? How can a DM and a single player play together? How can a DM or player play alone?

The truth is we do this all the time. We're playing D&D every time two people talk about their characters together or work together to develop a backstory. We play every time the DM and a player go back and forth in a scene while they happen to be chatting over lunch or during a walk.

We're playing D&D every time we're bored at work and thinking about what our villains might be up to. We're playing D&D every time we sketch out a ruined castle surrounding a hooded obsidian statue.

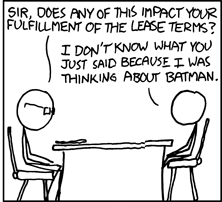

D&D is far more than just the game at our tables, although that's the most important part. D&D games are the stories and adventures going through our heads all the time, if we give ourselves the freedom to let them do so.

We often don't think about these activities as "playing D&D" and we certainly don't refine them like we do the other parts of the game, but there's no reason we can't.

Let's look at a few ways we can play D&D anywhere. We'll start with some solo activities for DMs and then move on to the activities players can do. This is, of course, not an exhaustive list, but just a handful of ideas.

Thinking Through the Eyes of our Villains

No matter where we are, we can always unfocus our eyes for a moment and ask ourselves "what is our villain up to right now?" This is a great way to think of our villains as living breathing entities. We're not plotting stories with this, we're watching the balls collide on a huge pool table. Villains act and react to the actions of the characters so our thoughts about the villain's reactions likewise keep our thoughts on the actions of the characters themselves—where they should be.

Thinking through the eyes of our villain is a fantastic way to play D&D because we can do it wherever we are, without any materials in hand and, even better, no one even knows that we're doing it. We're using the most complicated computer we know of, the human brain, to build a living and breathing simulation of our villains, and watching this simulation behave as the villain really would.

Moving Fronts Forward

While we're daydreaming through the eyes of our villains, we might begin to move forward their plots and their quests. We can steal the idea of Dungeon World's "fronts" and think about how the threats of these villains are moving forward. Here's a great thought seed for our mindful D&D game:

- What three villains are in our current story?

- What are each of those three villains doing right now?

- What goals do each of these villains have?

- What terrible plots are these villains pushing forward?

Those questions could fill up an hour of daydreaming and at the end we'd have something cool and useful for our game. Maybe we write this stuff down or maybe we just put ourselves to sleep at night thinking about it. This stuff isn't set in stone. We can let it come to life or we can let it morph the more we think about it. It doesn't become true until it takes form at the game table.

Outlining Secrets

In case you haven't heard, sharing secrets is a fantastic technique for building clues our characters can discover in our next game. Better than overall worldbuilding, secrets are small, bite-sized pieces of information and lore directly relevant to the characters and the world around them. We can use secrets to reveal mysteries, add or reinforce story seeds, share bits of interesting history, build deeper NPCs, or use for many other great purposes.

Coming up with secrets for our games is a great way to play D&D away from the table. Like many of the other techniques we've described, much of it can be done in our own minds with nothing at all. When we get a chance, we can jot them down in a notebook or on a 3x5 card and then review it during our next game.

Building Fantastic Locations

Our minds have no limits when it comes to building places too. Building out entire worlds might end up wasting brainy clock cycles but building interesting places for our characters to visit could be very useful. These locations can move around depending on what choices the characters make and we can always keep them on hand when the time is right to whip one out.

Thanks to our Kickstarter backers, we wrote a whole chapter in Sly Flourish's Fantastic Locations about building fantastic locations. Here's a quick summary:

- Come up with a big picture theme for the place. Mix and mash up ideas. Make it big in scale.

- Describe three or more rooms, chambers, or smaller specific places in this location.

- Choose three interesting features for each of these eight places.

We can even cut this down to just worrying about a single small location, a set-piece if you will, and the three things that make it interesting. It's a fun five minute mental exercise.

Outlining Flash Fiction

When we're not able to get to the table, sending out some flash fiction is a great way to keep the group connected to the game and even show them some things they might not otherwise know. Flash fiction, bits of in-story fiction at 500 words or less, can take us outside the perspective of the characters and into the eyes of someone else.

Flash fiction works hand-in-hand with seeing through the eyes of our villains and moving fronts forward. Our players can directly see what our villains are up to without the characters necessarily knowing themselves. Alfred Hitchcock called this the difference between suspense and surprise. In a surprise scene, a bomb might go off. In a suspenseful scene, the camera pans down to the bomb sitting under the chair of our hero. We know its there but our hero does not.

As many of us have experienced, trying to keep mysteries a secret from smart players is hard. Keeping them in suspense, though, when they see that Strahd is about to unleash the hordes of darkness throughout Barovia, that's powerful.

The key to great flash fiction is knowing, specfically, what we intend to reveal. This is the D&D we can play in our heads. Sure, we want our players to see what Strahd does after the characters kill Baba Lysaga. What specifically does he do that they'll care about?

- He introduces the Brothers, two powerful Vampire Bloodknights.

- He unleashes a horde of Feral Vampires.

- He plans to meet with Madame Eva directly to convince the Vistani queen to give over Ireena before even worse troubles arise.

Those are the sorts of things we can noodle through in our head and, when we have a moment, peck out in an email and send off to our players between sessions.

Playing D&D with Two People

If you happen to be with another player, either a player and a DM or two players, you can still play this head-space version of D&D. The two powerhouse questions here are "what does your character do?" and "what did your character do?" One is better for a DM and a player. "What does Beringar do after Strahd's confrontation outside of Argynvostholt?" might be the DM's question to Beringar's player. "I shapeshift into a wolf and explore the woods around the castle," might be the answer. "You easily follow the tracks of Strahd's wolves. You note that they all seem to head north. One of the wolves leaps upon a rock and sniffs at the air to the south. It whines quietly, its tail going between its legs as it peers out to the storms surrounding Mount Grakis, and then dashes north to the safety of Ravenloft."

No dice needed. No other players required. No fancy-ass Dwarven Forge arrangement on the table. Just two people talking, sharing a little bit of a story, and it's all some fine D&D going on.

What about handling interesting loot?

"As you return to Argynvostholt, you see the body of the revenant, the one that Strahd's vampire knight disarmed and killed. It is pierced through its black armor with a greatsword, pinning it to the ground in a kneeling position. A white mist seems to swirl around the blade. What do you do?"

"I take the sword!"

"A your hand grasps the black leatherwrapped hilt, you feel a deep chill travel up through your hand and a voice speaks in your mind. 'I awaken.'"

"Vengeance. Cold Vengeance."

"It would appear you have found the name of the blade."

You probably want to be careful handing out loot in a scene like this, but if you know it won't piss off the other players, it can be a fun way to get in some item-based storytelling with just a player and a DM.

Developing Player Characters

What if you're a player on your own? What can you do to play a bit of D&D in your head? There are lots of ways players can build out their characters, in backstory, side adventures, or just their own version of "seeing through their eyes". Some refer to this style of play as blue-booking, a term I hadn't heard of until researching this article.

If you really want to make your DM happy, as you develop your character's backstory, find a way to hook into the adventure the DM is already running. Find elements that have shown up in the game and discuss them with the DM. Play your own improv version of "yes, and" with the DM, giving the DM some room to guide your background around elements of the adventure. This can be done in email or in face-to-face conversations.

As a player you might also work with other players to tie your backgrounds together. A bit of improv "yes, and" between the two of you. Like above, you can then work with the DM to tie the results to elements of the game, building out a rich tapestry of deep stories, side quests, and interesting threads to explore.

Manage Your Expectations

All of this D&D playing we're doing in our heads is fantastic and fun, but we can't expect that everyone, or even anyone, at our table is going to be into it as much as we are. As both DMs and players, it behooves us to manage our expectations about how involved others will be in what we come up with.

As a DM, we shouldn't expect that our players will hang on our every word of flash fiction we email to them between games. We all have busy lives and that bit of flash fiction might just not make the cut when our players are triaging all of the stuff they have to do every day.

Likewise, as a player, we shouldn't be disappointed if our DM doesn't absorb every ounce of our character's background and incorporate it into the game. DMs have to manage a lot of story threads including all the villains, the fronts, the general plot of the adventure, and each of the characters.

Some DMs work hard to incorporate the backgrounds of characters. Some just plain forget to do it. And some instead really focus on the adventure itself and spend little time at all thinking about the backgrounds of the characters. That doesn't make them terrible DMs or the game a terrible game. It might still be a lot of fun. But its unlikely that the DM will love the thirty pages of backstory you developed if they'd rather worry about the text of the published adventure.

Overall we're best off managing our expectations and remembering that, as passionate as we are about our own little D&D games going on in our heads, others may not be nearly as passionate about them as we are.

Changing How We Think About D&D

Many of the things we've discussed are already well known. No one needs an article to tell them to "think about D&D" like it's some sage-like wisdom. More importantly, we can change our focus and redefine what we think of as "playing D&D". It gives us permission to let our minds wander and know that we're still deep into our hobby. It might give us a clearer framework for how we let our minds work on the game.

In this crazy age and with this crazy hobby, thinking is working and how we spend those brain cycles matters. When we consider that our time spent thinking about D&D is the actual act of playing D&D, we might end up a lot happier with how we're spending our time. No matter where we are, we can let our minds pierce through the fabric between worlds and enjoy what we find on the other side.

Related Articles

Share this article using this link: https://slyflourish.com/playing_dnd_anywhere.html

Subscribe to Sly Flourish

Subscribe to the weekly Sly Flourish newsletter and receive a free adventure generator PDF!

More from Sly Flourish

Sly Flourish's Books

- City of Arches

- Return of the Lazy Dungeon Master

- Lazy DM's Companion

- Lazy DM's Workbook

- Forge of Foes

- Fantastic Lairs

- Ruins of the Grendleroot

- Fantastic Adventures

- Fantastic Locations

Have a question or want to contact me? Check out Sly Flourish's Frequently Asked Questions.

This work is released under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International license. It allows reusers to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the material in any medium or format, for noncommercial purposes only by including the following statement in the new work:

This work includes material taken from SlyFlourish.com by Michael E. Shea available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International license.

This site may use affiliate links to Amazon and DriveThruRPG. Thanks for your support!